Chou Meng-tieh - The Coming of Tulku

Poet Ascetic

A Lone Peak Among Poets

The ancient Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou turned into a butterfly in his dream, where reality and fantasy were blurred. The poet dreamed of transcendence in the secular world and permanence in a life as fleeting as the morning dew or a lightning flash. Borrowing from Buddhist scripture, The Coming of Tulku captures one short day in the life of Chou Meng-tieh as a metaphor for an entire lifetime. Scenes of his daily life are interspersed with reflections on his thought, spiritual practice, and writings. The documentary recreates the atmosphere of the old Wu Chang Street, and the lonely kingdom that was Chou’s bookstand. It traces how his sickness both changed and enlightened him, and the exile and migration that he was forced to undergo and their meaning. In the end, his was a life of enlightenment and emotions, in which he remained loyal to both the Buddha and his loved one.

Chou wrote more than two hundred poems in his life, and published three volumes of poetry: Lonely Kingdom, Grass of Returning Souls, and Thirteen White Chrysanthemums. He once said that “writing poetry is painful,” but writing poems was the lone salvation in his hard and lonely life. Others see Chou as a man of few desires, yet as his close friend Chen Ling-ling reveals in the documentary, “Master Chou was in fact very sentimental; at times devoted, sometimes loving many.” Chou described himself as “filled with thoughts of romantic love” before he began studying Buddhism, and “wrote a few lousy lines of poetry precisely because of a tempestuous emotional life.”

Poetry in the Life of a Street Vendor

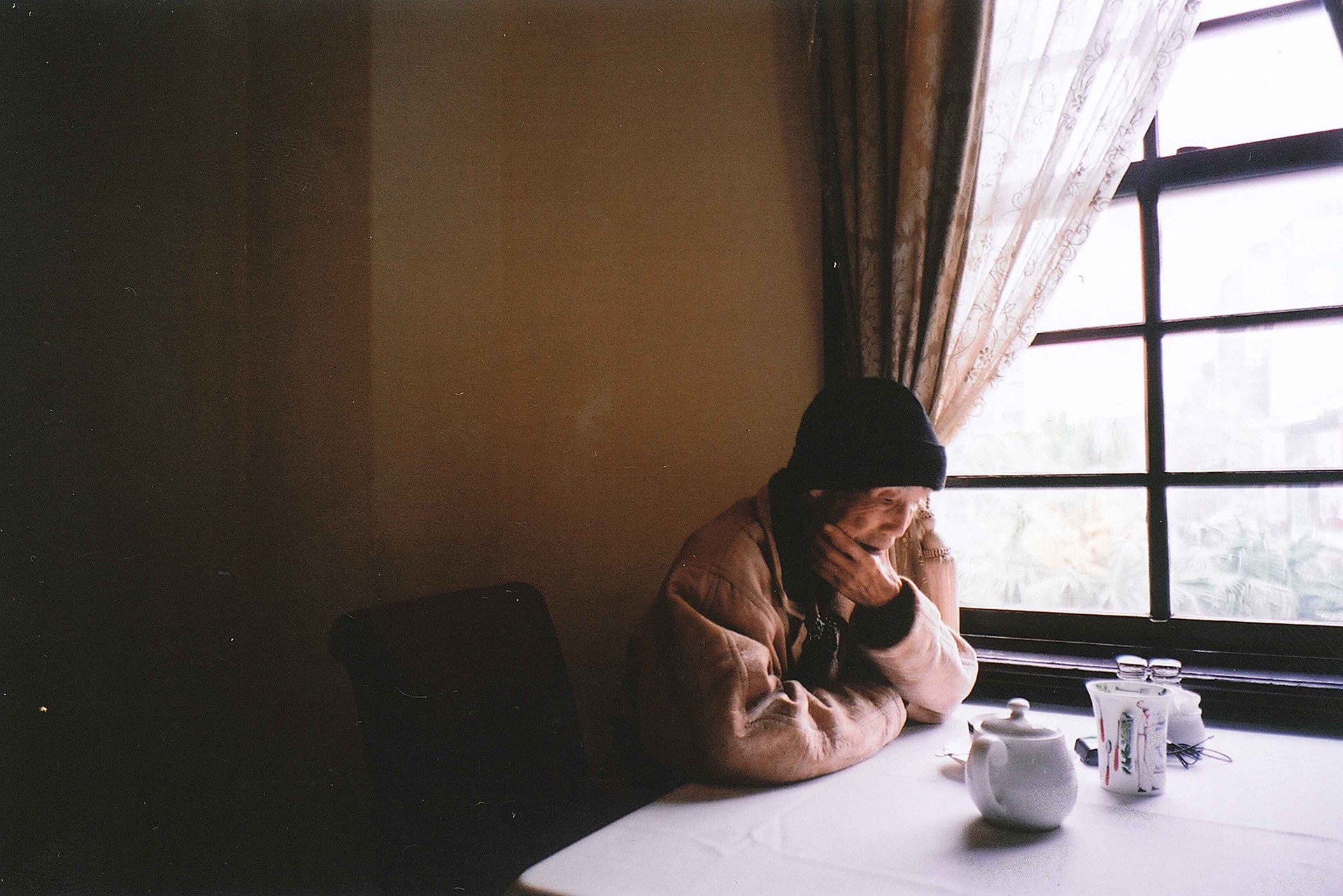

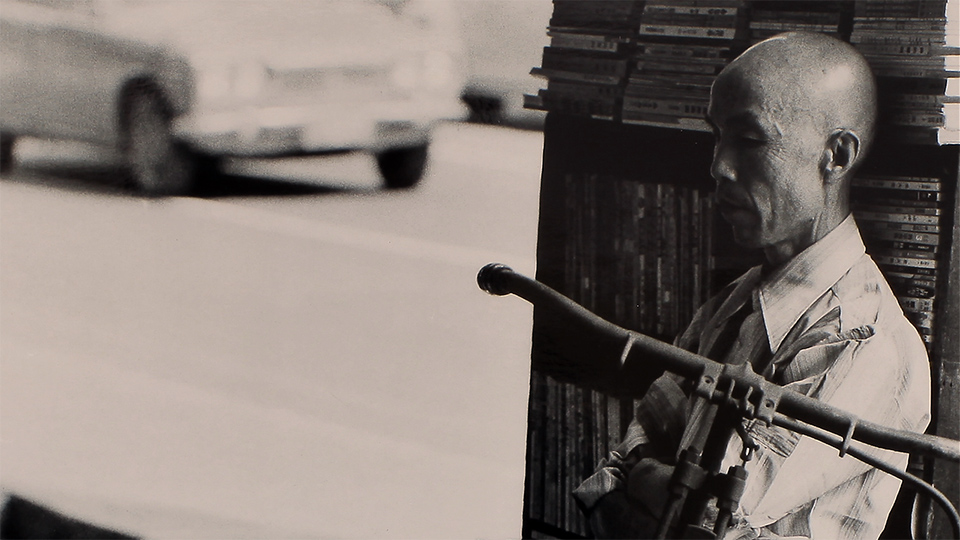

A long robe, a knitted cap. In 1959, Chou Meng-tieh began running a book stall in front of the Astoria Café on Wu Chang Street, becoming an important cultural scene on the streets of Taipei in the 1960 and 70s. A cool, lone, seated figure on the bustling city street, there he wrote those brilliant lines of poetry that won the hearts and souls of many. In the documentary film, he describes how he used to arrive early in the morning on the first bus of the day to tend to his “lonely kingdom”, which was “the size of all of four tatami mats, containing 421 books.” A profit of 30 NT a day was considered a “pass” by him.

The poet Yu Guang-zhong, a mentor and friend to Chou, once said: “Chou Meng-tieh is filled with contradictions, longings and discontent, but the world of poetry makes up for it all. Reserved and unfree in the real world, in the imaginary world he wanders, carefree, in the lonely kingdom.”

“When the whole world laughs, I might weep alone; when the whole world weeps, how have I the heart to laugh alone—you say”—— Chou Meng-tieh

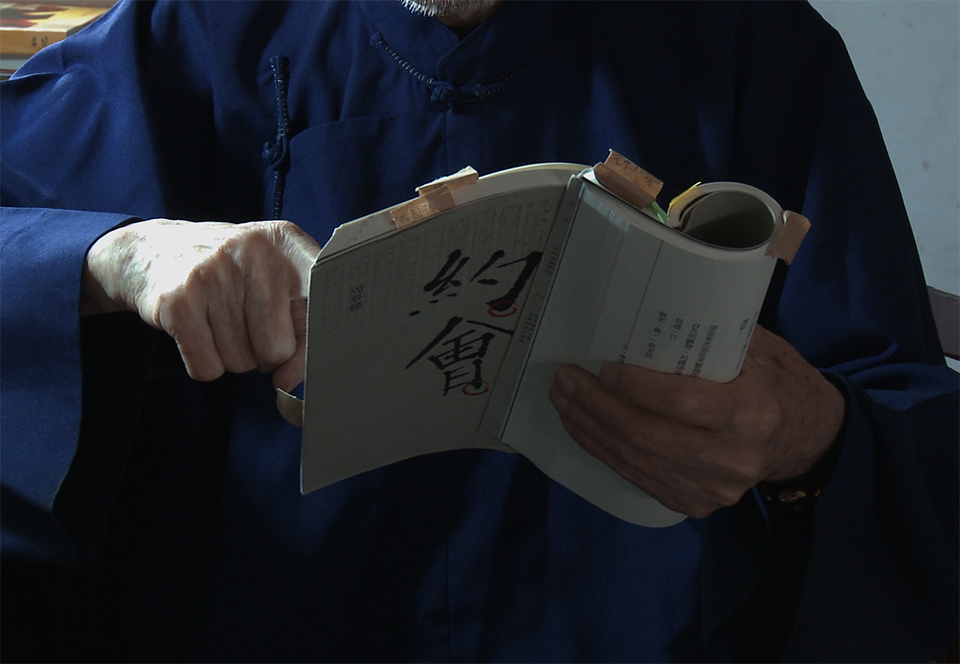

During a chat with Wei Zi-yun, known for his study of The Plum in the Golden Vase (a classic of Chinese literature), Chou Meng-tieh noted that although his poems often reference Zen and Buddhist ideas, in spirit they are secular. Often found in his poems are nods to The Dream of the Red Chamber and its protagonist Jia Baoyu, a sensitive and sentimental young man. According to Yu Guang-zhong and Weng Wen-hsien, Chinese professor at National Cheng Kung University, Grass of Returning Souls, which cemented Chou’s place in poetry, was a “collection of love poems”. In a letter to a close friend, Chou once recalled: “…Once I was feeling ill. I met a girl surnamed Yang, a sixth-year medical student at the National Taiwan University, on the third floor of Astoria Café. Before our meeting even ended, my discomfort had melted away as though hot soup had been thrown on snow. Now this girl has married and gone to America, and borne many children. Separated by distant seas, we shall never meet again. Will I never be cured of my chronic disease then? I can only laugh.” This offers a glimpse into his sentimentality. And as Yu Guang-zhong claims, perhaps rather than the philosopher Zhuang Zhou reincarnated, Chou is the sentient stone that entered the mortal realm as Jia Baoyu in The Dream of the Red Chamber, come again to this world.

Well versed in classical Chinese literature, Chou Meng-tieh often employs literary references in his poems. Deeply influenced by his study of Buddhist sutras, he also infuses his poems with Zen thought. His poems are graceful and poignant, and he treats the people, scenery and objects that he is nostalgic for with cautious tenderness. Although there are strong expressions such as “taking fire from snow, casting fire into snow”, there is also the tender willingness to become a fallen leaf on the street corner.

Director Chen Chuan-xin

Chen Chuan-xin received a PhD in Linguistics from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in France. He is the founder of Editions du Flaneur, and oversaw the translation project of Vocabulaire de la Psychanalyse. His documentary works include Immigrants, A Kun, Zheng Zhai-dong, and Narrative Biography of Yao Yi-wei. He is often invited to international symposiums to present papers on film and photography, winning enthusiastic response from scholars for his unique perspective and insights.

More Photos from the Set

Runtime: 163 mins.

Chou Meng-tieh the person is the best part of the documentary. His purity, personality and candor are endearing.

——Online comment from Y

His restless interior and extremely reserved exterior have led not only to a life of solitude and wanderings, but sculpted him into a unique figure.

——Online comment fromInkstone of Time

To hear that deeply accented and delicate voice read “Ten Good Lines” is to be suddenly enlightened, as though by some divine being.

——Online comment from 2+2=5