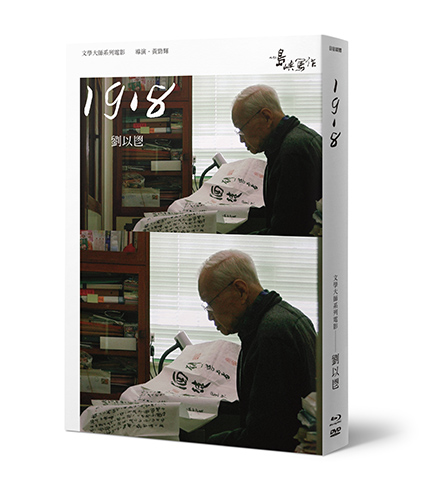

Liu Yi-chang - 1918

Long Stream of Consciousness and Modernity

All Memories are Sodden.

Reality adheres to memory like glue. The palm leaf fan in mother’s hand fans the stars Vega and Altair on either side of the Milky Way into brightness. On the day of snowfall, people with bamboo sticks in hand circle the fireplace and dance. (From The Drunkard)

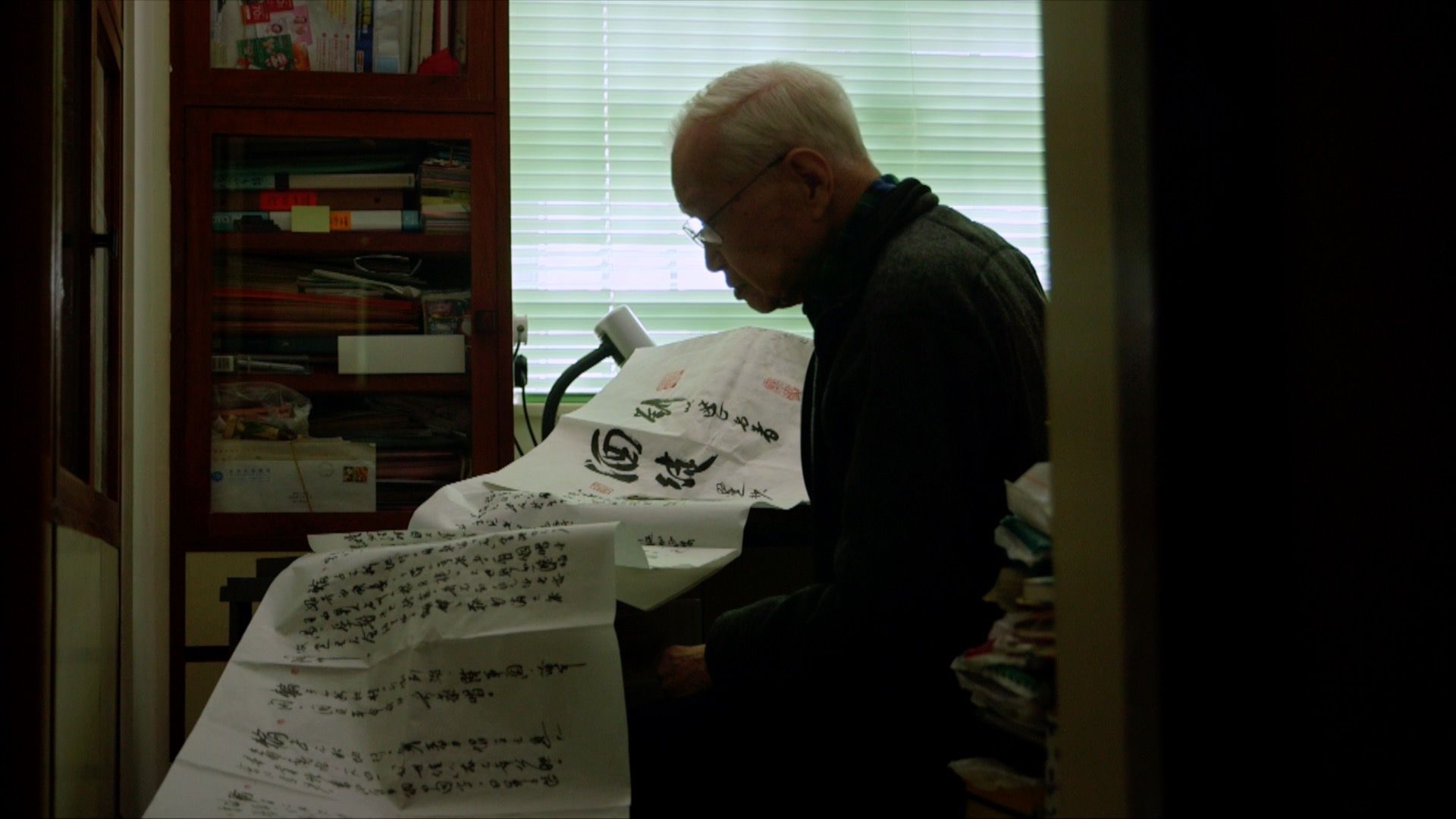

Born in 1918 in Shanghai, Lui Yi-chang is a witness of the modern Chinese literary scene. Only two years older than Eileen Chang, Liu achieved fame relatively late in life: he was over forty when The Drunkard was published. The turning point in his literary career and life can be traced back to a love affair in Singapore, so the documentary film crew traveled there and found the place where he and his wife had met, reliving that time in their lives in the actual setting. The film takes viewers into the creative world of Liu Yi-chang, getting to know the cities that he wrote about, traveling between real places and fictional worlds, from the modern city of Shanghai in the 1930s and 40s, southeast Asia in the 1950s, to Singapore and Hongkong, two cities that blend old and new charms. It is a trip that shuttles viewers between the fictional and the real, and the literary spaces of the past and the present…

“Since arriving in Hong Kong from Shanghai, I have relied on myself and my pen, producing some ten thousand characters a day. During the day I write things for the entertainment of others, at night I have time to write the things that I enjoy.”—— Liu Yi-chang

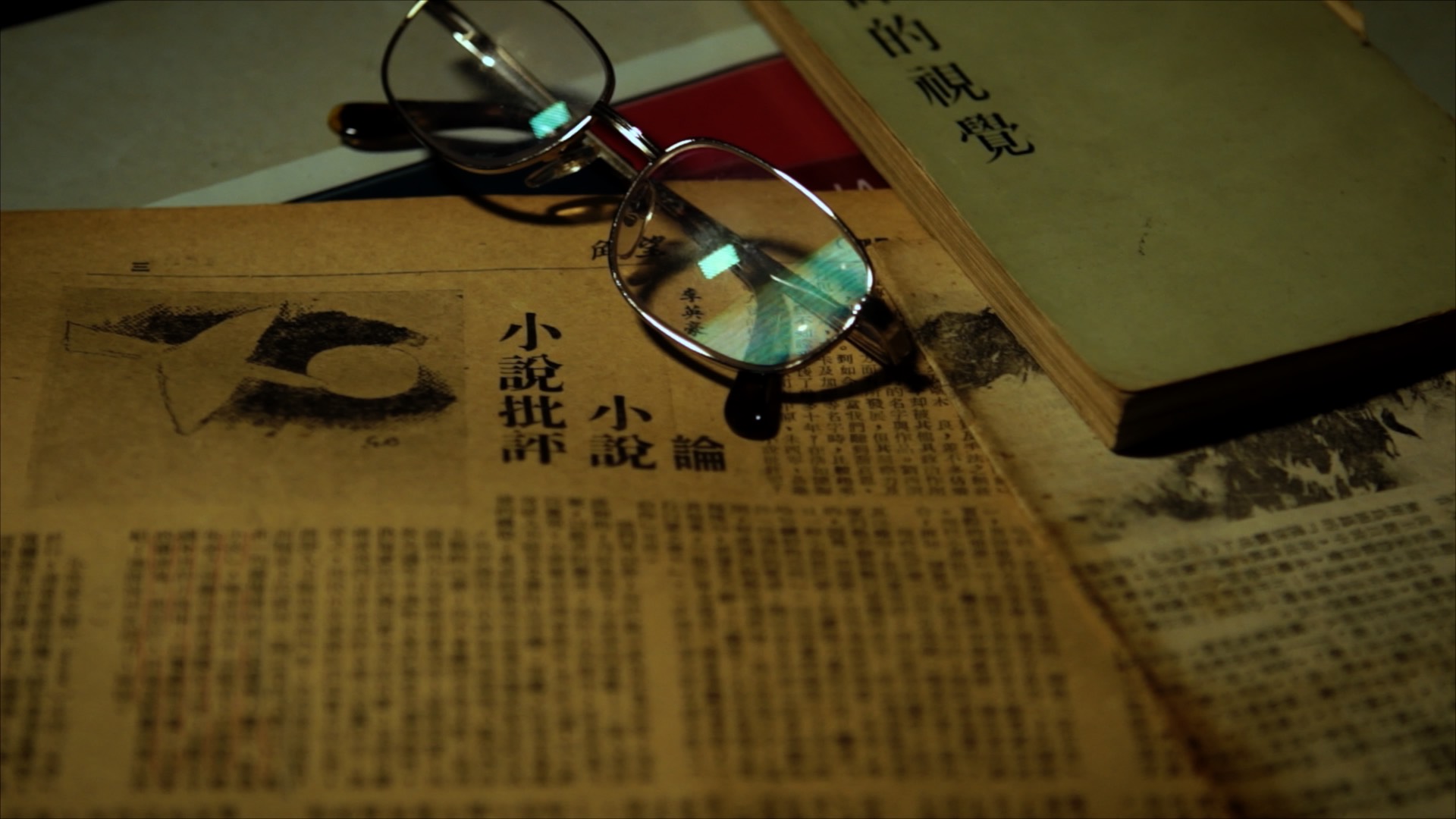

Literary Editor and a Friend of Newcomers

Liu Yi-chang (1918~2018) was born in Shanghai, where he later graduated from St. John’s University. He then went to Chongqing to edit the literary supplements of the National Gazette and Saodangbao (“eradication”, an anti-war newspaper), which marked the beginning of a life-long career in newspapers and literature. The civil war between the Nationalists and communists in mainland China drove him to Hong Kong in 1948, where he would work as an editor for various newspapers and periodicals, including the Hong Kong Times and Sing Tao Weekly, and write serialized novels to support himself.

In 1985 he started the Hong Kong Literature monthly, for which he served as editor-in-chief until 2000. Throughout his career, he lent a helping hand to many new-generation Hong Kong writers, giving them a place to shine in newspapers and the literature monthly. Even King-Fai Wong, who directed this documentary film about Liu Yi-chang, says Liu is “half a teacher” to him, because although Liu never taught him in a classroom, his influence was far and wide. Always willing to help aspiring writers, he would publish their first stories, sometimes calling them to offer advice or just to discuss the work. All this despite Liu once saying in a newspaper interview that “writers interested in literature will start writing on their own.”

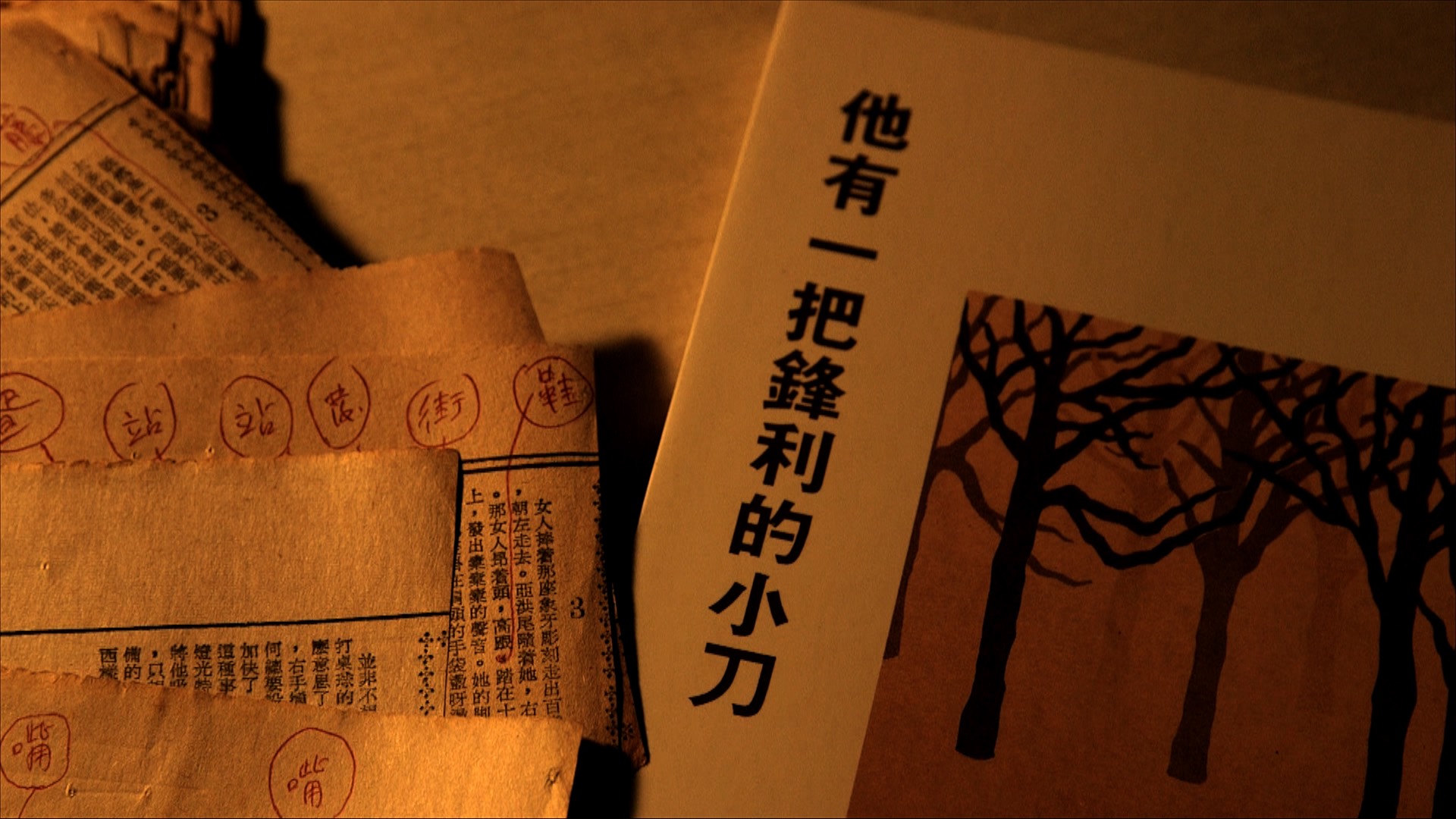

The Drunkard and Tête-bêche Inspire Later Movies

Liu Yi-chang is best known for his novels The Drunkard and Tête-bêche.

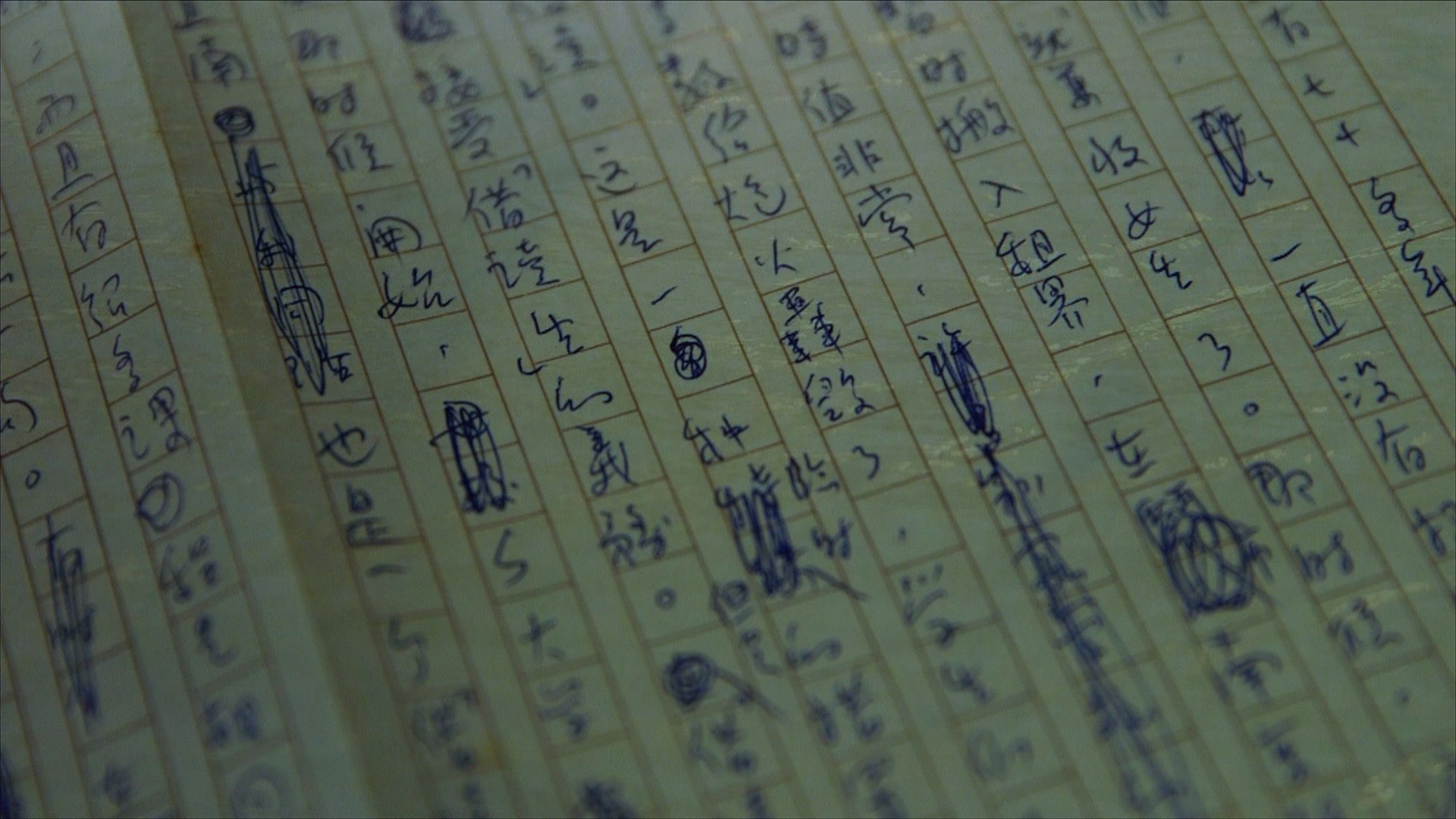

Written in the 1960s, The Drunkard is one of the most representative Sinophone stream-of-consciousness novels, and represented, at that time, a strongly experimental literary attempt. In a starkly modernist style, the novel captured the uncertain and utilitarian atmosphere of Hong Kong society at the time. The protagonist is a writer who wishes to write his ideal work of literature, but is forced to cater to popular tastes, writing popular and even pornographic novels to make a living. Torn by his scorn for himself, he seeks refuge in drinking and feels sick of the world.

Tête-bêche (also translated as “Intersection”) is a story of romantic love, and the kind of sorrow and fleetingness uniquely associated with romantic love. Two people whose lives seem like they might never intersect sometimes exhibit the same behaviors, enjoy the same things, travel to the same space, even look into each other’ s eyes, but remain strangers. Liu Yi-chang is a master of the internal monologue, presenting a potentially explosive plot with a gentle tension, coolheadedly telling the story but creating pockets of sentimentality in what is left unsaid.

World-renowned filmmaker Wong Kar-wai based two of his movies on Liu’s novels: 2046 (The Drunkard) and In the Mood for Love (Tête-bêche).

The Hong Kong Arts Development Council recognized Liu’s contribution to Hong Kong culture and literature with the Award for Outstanding Contribution in Arts in 2013 and the Life Achievement Award in 2015. As a literary mentor to many over a century, Liu Yi-chang lived through and bore witness to an important era in the development of modern Chinese literature.

Literature is art, and art is the means by which the writer creates images. Therefore, a work of literature must contain artistic qualities. It should not be content with representations of life in the external world, but should rather represent conflicts of the internal world.—— Liu Yi-chang

Director King-Fai Wong

Devoting himself to the creation and study of literature and films, King-Fai Wong experiments by incorporating elements of literature into movie making. His screenplay for Life without Principle (2012), which drew from the literary technique of multiple narratives and points of view, won Best Original Screenplay in Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards and Best Screenplay at the Chinese Film Media Award, and was chosen as Best Screenplay by the Hong Kong Film Critics Society. The movie itself won Best Picture at the Asia Pacific Film Festival. Wong has a Ph.D. from Shandong University’s College of Literature and Journalism. He edited the “Literature and Film” book series published by Hong Kong University, and has published two collections of short stories. His latest work is a full-length novel as he continues to explore the relationship between images and literature.

More Photos from the Set

Runtime: 55 mins.

1918 can be described as the most effortless of the “Island series” documentaries. Or, rather, much effort went into it but the whole film came together seamlessly.

——Online comment from blogger Xiao Bu

An avant-garde old man who loved literature, model-making, stamps and ceramics.

——Online comment from Ienvis

Great film. Uncultured as I am, I enjoyed it. If you like Hong Kong and Wong Kar-wai, you will too.

——Online comment from Xiang xiang